Becoming A Big Man on Ambrym Island in Vanuatu

Scarcely touched by the world outside, Ambryn Island is one of those places where villagers shun the modern world and live according to the ways of their ancestors. Join Glen and I to discover how village men in Vanuatu gain rank within the tribe.

I stood on the bow as Glen dropped anchor in front of a village on Ambrym Island, in Vanuatu. Black coral sand lined the shore and small thatch huts stood in a clearing cut out of the green, jungle-thick hills. The only villagers in sight were small, naked children somberly studying our sailboat, shifting their gaze from the waterline to the top of the mast. Not much has changed here since Captain Cook, I thought, waving and smiling. Instead of waving back or laughing, the children looked down and scampered quietly away.

Joining Glen at the stern to lower our dinghy, “At least they’re not crying at the sight of my red hair, like the last island.”

There were few visitors to Ambrym and little contact with the modern world. People there live according to what they call kastom, or old ways. Homes are extensions of the jungle, built beneath sprawling banyan trees, their girth large enough to withstand fierce tropical cyclones. The village looked deserted now that the children had run off, peeking out from behind the trees. Then, before I could call out, I spotted a tall, thin, ebony-black man watching us motor our dinghy to shore.

For me, this is the most exciting time at a new place. Those first moments when our words, actions and manner would either draw us in to the life of the village, or sideline us with civil, yet standoffish, welcome. Things looked promising so far. The villager met us on shore and introduced himself in English as Eli, recently returned from Australia where he worked for decades as a laborer. He wore shorts secured by a rope around his waist and a cast-off T-shirt with the imprint of a 10K running race in Eugene, Oregon. Eli lived in Port Vila, the Vanuatu capital, and was on Ambrym to attend the chief grading ceremony of a cousin.

Our Man on Ambryn

“It is very interesting,” said Eli. “The kind of thing white people like to see. I will ask my cousin if you can stay. Maybe 25 or more pigs will be killed—people are coming from other villages.”

“Eli, we would love to understand more of your culture. Please ask your cousin.”

Looking around, I asked, “Where is everyone?”

“They are gathering kava, cassava and yams for the feast,” he said, inclining his head toward bundles of gnarled, dirt-caked kava roots piled on the red earth beside a dirt track. Banyan trees lined the path all the way to the clearing where we stood, their limbs shading us. A large black bowl stood in the center, ready for kava.

Ah, kava. Kava is an important part of the traditional culture of Vanuatu. Kava comes from a plant that grows wild in those islands and I cringed at drinking more of the foul-tasting brew. After a couple coconut shells of strong kava, villagers loosened up and talked freely about, well, everything. But even the tiniest of sips affected me so greatly all I could do was smile stupidly and admire the pretty stars.

Eli motioned for us to sit down in the shade of a banyan tree, sheltered from the sun but soon attracting mosquitos. Preferring to be a moving target for the dengue mosquitos that graze during the day, I asked Eli if we could take a walk to stretch our legs.

Wiry Eli jumped up, eager to guide us, cautioning us to only travel the paths with a native guide. “Only walk here with villager. Not go alone.” It made sense. The surrounding bush was their back yard. I thought about how prickly westerners are when people trespass into their yard.

Walking the hard packed dirt path, we paused with Eli as he pointed out a half dozen tall, hollow, wooden logs he called tam-tams. “You call them drums. You will hear much drumming very soon!” he said, laughing. “You may not be able to sleep.”

Shortly we passed men carrying loads wrapped in burlap cloth, one who stopped to speak to our guide in Bislama—the pidgin English spoken in Vanuatu. “Mo hu ya man?” Which I took to mean “Who are they?”

Eli answered something like, “Blong America e mas visitem boat. E joen long seremoni ya.”

Trying to understand Bislama was like listening to a conversation in English from behind a closed door; a little garbled, but possible to get the meaning. It sounded like Eli was explaining our presence. The villager shifted his bundle, shrugged and took off in the direction we had just come. Eli then led us to an enclosure of medium sized pigs and one enormous, feisty-looking pig tied to a tree close to the rough wooden pen. The pig looked fierce, snorting at us while eating a pile of yams.

Pigs Are Like Currency

Pigs on the out islands of Vanuatu hold a status difficult for westerners to conceive; somewhere between sacred and the equivalent of money in the bank. The one in front of us intent on its meal of yams paused to look up, defying us to interrupt him. Eli called the pig Porky, but it did not look like the cute cartoon character. More like a battle scarred wild boar. Coming between that porker and his food was the last thing on my mind and the three of us stood at a respectful distance from the enormous creature.

Eli spoke of the importance of Porky in the upcoming chief grading ceremony, pointing out its fierce looking tusks. Inspecting closer, I shrunk back at what I saw. “Oh my. No wonder it looks mean,” I told Eli. “The tusk has made a complete circle and is going for another through the pig’s face.”

Eli told us that such fine specimens were created by knocking out the pigs’ upper teeth to let the tusks grow free. Such tusks were family treasures. “This pig will be given to the head chief for sacrifice,” said Eli. “Many men are coming to see this pig die,” and explained the chief grading ceremony as a way for village men to work their way toward becoming the overall chief.

Chief Grading Ceremony

But it took a lot of pigs to become even a lesser Chief. During the ceremony his cousin Ati would be promoted to the 8th of 13 levels necessary to become the high chief. Ati would be “giving pigs—many pigs—to the high chief” for the honor of being advanced to the new level.

“What happens to the pigs?” I asked.

Eli said that in a sacred ceremony, using a special club and knife, enough pigs would be killed to feed all the villagers who came to the celebration. “You will see,” he said. Not wanting to see pigs clubbed to death, I squeezed Glen’s hand, who squeezed back in understanding.

“In Vanuatu, pig is both sacred and money,” said Eli. Nodding toward Porky, “That pig is sacred because it exists for sacrifice and my cousin has to feed. When the chief kills it for the people to eat, it has value.”

“Are you saying that a pig only has value to the owner when he gives it away?” I asked Eli.

Nodding, Eli answered, “You can trade it for something valuable, but if you eat your own pig in secret, you are a small man. If you kill it for others to eat, you are a big man. Worthy of becoming a chief.” He explained that pigs are symbols of wealth and required for marriage. If a man wishes to marry a girl, he must pay the father eight pigs, “more if she is very beautiful or comes from a family with many pigs.” “There are many unmarried men in Vanuatu,” said Eli shaking his head.

“Are you married?” I asked.

“No. I am maybe too old now but have money from working in Australia to buy many pigs. And I live in Port Vila. Pigs are only money on the islands. In Port Vila people use paper money. If I return here, my money will be gone very fast.”

The irony of Eli’s situation struck me as brutal. He had ventured out to the larger world to make enough money to buy pigs for a wife. Only it took so long that he returned with different values. He lived in Port Vila because he was afraid to go back to his village. Looking around, I understood that he would be stripped of his nest egg by the equality-minded island code. After all, each villager had access to the same coconuts in the trees, yams and kava in the jungle and fish in the water. Why not share money with those in need? Even their grade-taking ceremony seemed a way to redistribute the wealth of a villager who had more than others; pigs given in tribute would be consumed by all. It seemed a brilliant way to keep harmony within a village.

Like a Family Reunion

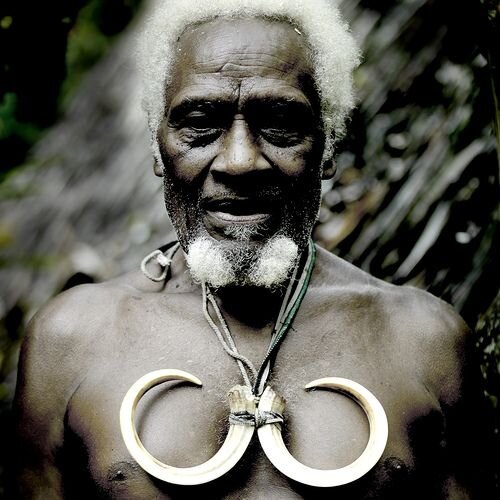

Villagers arrived by the dozen over the next two days, carrying bundles in repurposed burlap rice bags, and leading pigs, some with fierce tusks. The thatched huts and surrounding jungle absorbed the guests as numbers grew to the hundreds. Men gathered in groups, discussing what Eli described as “pig business”. Eli’s attire had changed from his rope-tied shorts to a white grass skirt and he sported a modest, half-circle boar tusk on his chest. He seemed to be known by all and passed freely among the clusters of men. The scene took me back to grade school where the boys and girls stayed on their own sides of the playground. The men discussed “pig business” while the women rehearsed a dance and song for the coming celebration. The repetitive words and tune to the song were so catchy I could not get it out of my head. Neither could Glen and we would burst out laughing when one of us started humming the tune with the chorale on shore. Even now, years later, I can easily recall the words and tune and only hope I can shake it.

Native Dancing

The morning of the chief making ceremony Ati, the host, greeted us with, "You are welcome here but please do not take a movie. Only a few photos.” This, of course, was a huge disappointment. Glen slowly put our video camera in his backpack. We would have to be content with his rule, but the sights and sounds begged for more than mere random photographs. Swirling lines of women, painted and adorned with chicken feathers in their hair, drummed, sang and danced to the catchy song we had heard over and over again during practice. The rest of the dancing was performed by a group of about 30 men that Ati circled repeatedly, chanting something that sounded akin to “these are my people.”

Most men wore the cast-off attire common in the islands, while some were more ceremonial and kastom with grass skirts and boar tusks—some that looped fully around.

As the only non-villagers, we were unsure where to go, but of course no one paid us any mind. So Glen and I sat on a log and watched the scene unfold. After hours of dancing everyone slowly came to a stop. Villagers lined the clearing, alerting us to some new phase of the ceremony. The high chief stepped forward and men on their way to raising a grade towards chief led pigs of all sizes as offerings. Everyone murmured in what sounded like appreciation when Ati led Porky, the biggest pig, forward—the one with a circling tusk we had seen in the jungle.

The high chief was bare chested, wore a wrap around his waist and a long, green fern sticking up from a western ball cap. A huge club lay at his feet. The chief had graying hair, and walked with a slight bow in his back. But he was muscular and looked perfectly capable of delivering a lethal blow to any pig or man. I will spare you the details of large pigs dispatched with a sacred club. Also, I can’t, because I had my eyes closed and heard rather than saw the sacrifices.

Finally, after a very long, hot and sweaty day the sun was getting lower. Villagers prepared for the feast that would follow, and it seemed a good time for Glen and me to return to the boat. Darkness came quickly, and celebration went on through the night with people dancing and laughing from one end of the well-trampled clearing to the other.

Back on the boat, Glen and I went through our evening ritual of installing fabric screens on the hatches and portholes of It’s Enough. Cruising in malaria regions required precautions. During the day we wore long sleeves and leg protection for protection against dengue mosquitos, and night was mealtime for the type carrying malaria. For us, retreating behind screens was an easy choice. The only antimalarial drug effective against the lethal falciparum type in Vanuatu had unfortunate side effects like paranoia and hallucination—an unwise option for two people on a small boat crossing oceans.

Processing the day, I wrote in my journal which was growing thick with sights, sounds and experiences beyond our imagination. Primitive Vanuatu kept me full of wonder that such cultures still exist and gratitude to glimpse a way of life that had nearly disappeared. Thanks for joining me on this adventure. Please come aboard for more stories of our around-the-world sailing adventures in Escape from the Ordinary and Crossing Pirate Waters.